Andrew,

Look what a dance reviewer in Minneapolis wrote about me a few months ago when I performed with the Lucinda Childs Company to music by Philip Glass: "My favorite dancer was a white-blond imp who smiled in every step, she was, a delight moving."

Lucinda Childs is (as you know) the grand dame of American modern dance. Touring the world with such a renowned choreographer would have been almost unimaginable to me when I sat down, despondent, to have dinner with you in early September 2001. It would have been even more unbelievable to me that I would, today, be launching my very own dance company -- Katherine Helen Fisher Dance (

www.katherinehelenfisher.com) -- and that the Huffington Post would call my company's recent performance "stunning, visually rich with color, architecture and movement."

For this, in a fundamental way, I have you to thank.

That early September evening that you invited me to dinner, I was in such a funk. I was one of thousands of struggling young dance artists eagerly attending every cattle call in New York City. I rode my bike across the Manhattan Bridge to save the $2.00 subway fare. I saved all my nickels, dimes -- even pennies -- in my rent-controlled Brooklyn apartment and would bring them to the CoinStar machine at the supermarket, to be converted into a few paper dollars so I could buy food. I had just been to another call-back without booking the job. I arrived at that little Italian restaurant in the Village exhausted from working odd jobs to make rent, from tirelessly training my body, and from trudging up six flights in loft buildings to attend unpaid rehearsals. I was looking frayed around the edges at best.

But I was so happy to see you, my father's brother, my favorite uncle. A successful financial analyst, you were dashingly handsome, well-traveled generous, and, most importantly, hilarious. You had just moved back to the city after a few years working in Sydney, Australia, and the whole family was glad to have you back.

That night you ordered us a lovely meal--for me, an extravagant treat. Over two bottles of Eco Domani, I opened up to you and told you I was ready to throw in the towel, I was ready to give up on my dream of having a career as a professional dancer.

You not only listened to my gripes with a sympathetic ear, you passionately encouraged me to persevere. You told me, "Don't give up!" You had always supported my dancing -- always attended my concerts through the years of training. Now you talked about all the great works of art and artists who had inspired you throughout your life. You spoke with such energy, it totally changed my mood from despair to resolve. I left the dinner, determined to keep going.

Just a few days later, you walked into a business meeting at Cantor Fitzgerald on the 104th floor of Tower One of The World Trade Center. Three days after that, in the midst of my-- our whole family's, the city, country, the world's confusion and grief… something amazing happened: a call-back I thought I had lost turned into a job: dancing in an off-Broadway show. That month, I wandered around dumb-founded in grief, but for the first time, I paid my rent by dancing. I know it was you, Andrew, who got me the job. There was some exchange of energy, as mysterious and transformative, as valuable as art itself -- that made your passionate wish for a turn of luck for me come true.

I am now a working dancer and choreographer with some of the country's most respected companies. And now, with my own work, I have traveled from Beijing to Rome and back.

The Minneapolis reviewer who praised my dancing in Childs' ensemble went on to say that "it was all alive to her and she made it alive to me." Andrew- you kept my dream to dance alive when no one else cared to nurture it. That gift, the gift of hope, lives on in my life and each day as I am driven to create.

With love,

Kate

(This letter an excerpt from a piece initially written for Glamour Magazine in conjunction with write Sheila Well)

About Seven Dolors:

Seven Dolors is a dance about keening. The piece observes the boundless, universality of maternal grief. In crafting the dance, I researched Russian iconography and incorporated it into the movement vocabulary via gesture.

The seven stages of grief, as codified by contemporary psychiatry, are spatially represented as

diagrammatic pathways within the proscenium framework.

The piece's title refers to the Seven Sorrows of Mary, a Roman Catholic devotion and key theme in Marian art. Enduring grief though ritual movement inherent in human kind's experience of loss, a mother mourns the loss of her son.

First choreographed in 2001, with the help of a Silo grant Seven Dolors premiered it at DanceNow.

The dance film Seven Dolors was shot in 2011 at an abandoned furniture factory in Long Beach, California. Eli Rarey directed the film.

Aftermath:

The world seemed to cease to exist even as life went on in surreal moments, not days but months. I lost my job as I went out to my family home in Bay Shore, Long Island to be be with my grandparents. A cookie cutter house built in the 50's, a part of the country's first planned communities. A house at the end of a cull-de-sac behind a strip mall flanking Sunrise Highway near the beach and the railroad.

At the house I found my place clearing plates and preparing food in some sort of numb, android-type space. I felt, very stingily, that Andrew was still alive, somewhere in the rubble in penny loafers and an Izod shirt. That he was biding his handsome time until one of those brave NYPD dudes would gruffly rescue him from the rubble.

Maybe that was true for a moment. It's a thought that still occurs to me as I wake up in the mornings in my more than one hundred year old rent controlled Brooklyn Navy Yard apartment building with cracks running though the foundation. As the building crews dig deep into the bedrock across the street of the 13 years ago county jail turned vacant lot. My room dances as if on circus stilts, my blinds swaying in time to jackhammers slowly plodding along a design which will transform earth into a glittering complex of condos with subfloors for parking smart cars with fitness centers and discount, organic shopping depots accessible from the BQE.

No such good news came to Bayshore. Aunt Christina came home from her post as a property manager for luxury Lake Tahoe vacation rentals and was wailing and screaming as she came in though the front door. It seemed like everyone in the family had a different way of coping with the grief of loosing the family's most successful and handsome son, one of six siblings born of a sheet metal worker who installed copper roofs on Manhattan skyscrapers (Local 183) and an Italian-American Simplicity seamstress turned housewife.

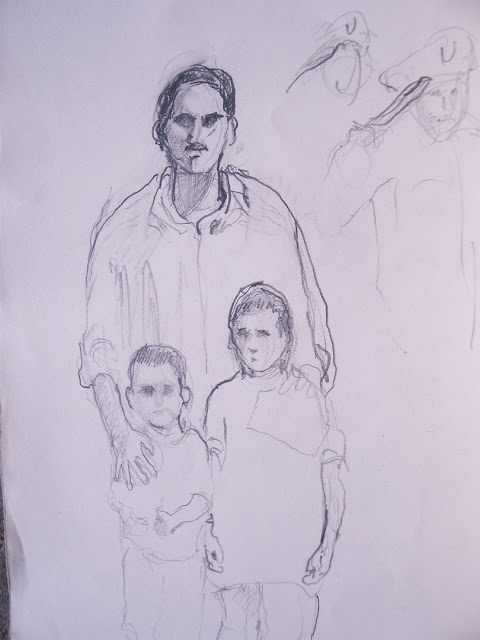

I watched with efficient dish clearing precision as it was past the point of staring, stunned at the television instead, I paid close attention to my grandparents who grew up during the Great Depression. My grandfather sat on the edge of his bed like an ancient modern frieze of a Atlas or Sisyphus. My grandmother though, she was different than any one else in the house.

In her grief, she danced, slowly, noiselessly rocking back and forth in the rocking chair in which she fed each of her children. Keening. Movement. Dancing through the memory of the life of her precious son.